Learn about BPCA Investor Relations including our News & Press Releases, Capital Projects, and Executive Team.

Talk to us

Have questions? Reach out to us directly.

Learn about BPCA Investor Relations including our News & Press Releases, Capital Projects, and Executive Team.

About BPCA

- Established

- 1968

- Bond Ratings

- Aaa/AAA

- Debt Outstanding as of 10/31/25

- $1,042,225,000

The Hugh L. Carey Battery Park City Authority (the “Authority”) is a public benefit corporation created in 1968 by the New York State Legislature to be responsible for planning, developing and maintaining the residential, commercial, parks and open space located along the Hudson River in Lower Manhattan in New York City (the “City”). Home to 16,000 people, the work place of 40,000 more, and visited by more than a half-million people each year, New York’s Battery Park City is an asset to both the State and City.

According to the Battery Park City Master Plan of 1979, Battery Park City was envisioned not to be a self-contained community, but rather a neighborhood woven into our city’s fabric. Through its contributions, the Authority is deeply committed to the mission of providing resources for the good of neighborhoods across the five boroughs.

Battery Park City Authority has a long history of environmental leadership. Since its inception, the parks and open spaces in Battery Park City were designed with environmental quality as a priority. In the early 2000s, the Authority released environmental guidelines for residential buildings and commercial buildings, leading to the development of buildings that were well ahead of city, and even global standards at the time. The BPC Sustainability Plan, released in 2020, builds on Battery Park City’s robust environmental legacy with a refreshed commitment to take and facilitate bold and effective action to enhance sustainability and reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. The Board and management of the Authority remains committed to encouraging and pursuing resiliency and environmental sustainability among its top priorities.

Through its layout and geographic orientation, Battery Park City is an intentionally knitted extension of the City’s streets and blocks. The names of streets heading east and west are purposely the same as those on the opposite side of West Street. Battery Park City was never considered an addition to New York City, but rather, a continuation of this dynamic City’s development into the 21st century.

Image Gallery

News

Governor Kathy Hochul, Mayor Eric Adams and New York City Comptroller Brad Lander today announced an agreement between the Battery Park City Authority (BPCA) and Brookfield Properties (Brookfield) to modify the ground lease for Brookfield Place, a 9.4 million square foot office and retail complex located in Battery Park City. The new lease terms, which secure higher ground rent payments and extends the lease term from 2069 to 2119, is projected to generate an estimated $1.5 billion of current value for the City of New York and for the Joint Purpose Fund, which supports affordable housing development across New York City as agreed upon by Governor Hochul, Mayor Adams, Comptroller Lander and BPCA.

“This agreement not only ensures the stability of Battery Park City while building and preserving more affordable homes throughout New York City — it also uplifts the city’s economy by securing Brookfield Place for years to come,” Governor Hochul said. “My administration will continue to work with our private, city and local partners to promote affordable housing, economic growth and deliver only the best for New Yorkers.”

New York City Mayor Eric Adams said, “From the most jobs in city history to historic amounts of housing, the Adams administration has been relentless in creating a safer, stronger, more affordable city. Today’s announcement with Brookfield Properties doubles down on our success, laying the groundwork for another five decades of economic growth and new homes. I often say that New York City is not just coming back, we are back and better than ever, and agreements like this one show why. We will bolster Lower Manhattan’s role as a job creator for the entire city while investing billions of dollars in the housing New Yorkers need. That is a win for our city, state, and private partners.”

New York City Comptroller Brad Lander said, “With this renegotiated ground lease, Battery Park City can increase long-term revenues through 2119 — continuing to thrive as an economic engine in Lower Manhattan — and continue to lay the groundwork toward financing affordable housing. Resilient design, environmental responsibility, and affordability are not trade-offs, but the blueprint for a fiscally and socially sustainable city for New Yorkers. Because of the partnership with the Governor, BCPA, and the Mayor, we are able to achieve progress toward our goals to strengthen economic activity, build affordable housing, and shore up the fiscal base in Battery Park City.”

This agreement underscores the continued strength of Lower Manhattan’s office market, of which Brookfield Place comprises approximately 10 percent of inventory, and builds upon Governor Hochul, Mayor Adams, and Comptroller Lander’s announcement in 2024 of a $500 million investment in the Joint Purpose Fund to build and preserve affordable housing in New York City.

Battery Park City Authority Chair Don Capoccia said, “Battery Park City Authority is glad to deliver this agreement for the future of affordable housing, for the future of downtown — for New Yorkers. I thank Governor Hochul, Mayor Adams, Comptroller Lander, our partners at Brookfield, and Raju and the BPCA team for securing this historic and impactful win.”

Battery Park City Authority President and CEO Raju Mann said, “This agreement is a powerful vote of confidence in the commercial vitality of New York. By extending and updating our lease structure with Brookfield, we’re not only ensuring the continued financial strength of lower Manhattan and Battery Park City but also advancing our mission to promote affordable housing citywide. We thank the Governor, Mayor, Comptroller and Brookfield for their partnership.”

Representative Dan Goldman said, “As we face a housing crisis in our city, I am grateful for this agreement between Battery Park City Authority and Brookfield Place that will add revenue to the Joint Purpose Fund ultimately contributing to increased affordable housing. BPCA and Brookfield Place share a common goal to invest and strengthen Lower Manhattan, and this agreement will support doing just that."

Manhattan Borough President Mark Levine said, “This lease agreement represents exactly the kind of creative partnership we need to tackle Manhattan’s severe housing shortage. By securing $1.5 billion for affordable housing development, this agreement transforms commercial real estate success into tangible impacts for working families across our borough and the entire city. At a time when countless New Yorkers are struggling with skyrocketing rents and limited housing options, today’s deal proves that strategic negotiations can generate substantial resources to build the affordable homes our communities desperately need.”

New York City Councilmember Christopher Marte said, “This agreement to renegotiate and extend Brookfield Properties’ ground lease is welcome news for Lower Manhattan and for New Yorkers across the five boroughs. By updating the terms and securing higher ground rent payments, we’re not only ensuring the continued presence of Brookfield Place but also generating critical revenue that can go directly toward building and preserving affordable housing citywide. It’s an important step forward for our community and a clear example of how smart partnerships can strengthen our local economy while addressing the housing crisis.”

New York State Homes and Community Renewal Commissioner RuthAnne Visnauskas said, “The financial stability created by this agreement will generate $1.5 billion that the State and the City can invest together to build and preserve affordable housing in neighborhoods across every borough, while also putting the pieces in place to ensure Brookfield Place remains an economic powerhouse for generations to come. The partnership of the Governor, Mayor, Comptroller and BPCA shows how the role of government in New York is generating results that provide critical benefits to residents and businesses alike.”

New York State Association for Affordable Housing President and CEO Carlina Rivera said, “This groundbreaking agreement is a model for how smart public-private partnerships can deliver real, lasting benefits for all New Yorkers. By leveraging one of Lower Manhattan’s premier commercial assets, we’re unlocking billions of dollars in funding that will directly support the development and preservation of affordable housing across the five boroughs. NYSAFAH applauds Governor Hochul, Mayor Adams, Comptroller Lander, and the Battery Park City Authority for ensuring that New York’s economic growth also fuels greater housing equity and opportunity.”

New York Housing Conference Executive Director Rachel Fee said, “Too often, the benefits of New York’s thriving real estate market don’t reach the families struggling most with housing costs. By securing stable revenues from Brookfield Place through this new agreement with the Battery Park City Authority and dedicating them to affordable housing, state and city leaders are ensuring that vital resources will be available to create and preserve the homes New Yorkers urgently need for decades to come.”

Alliance for Downtown New York President Jessica Lappin said, “This deal represents the kind of creative, forward-thinking partnerships we need and reflects the enduring vitality and strength of Lower Manhattan. The Downtown Alliance applauds Governor Hochul, Mayor Adams, Comptroller Lander and the Battery Park City Authority for their leadership in securing this agreement.”

The Battery Park City Authority owns the land in Battery Park City and has long term leases in place with the building owners in the neighborhood. In exchange for a longer lease term, Brookfield is committing to pay higher ground rents which will primarily flow to the Joint Purpose Fund and support the construction and preservation of affordable housing throughout New York City.

The agreement establishes a rent schedule under which the City and State benefit from the economic performance of the buildings, replacing the existing agreement that was formed before the commercial success of the complex was proven. The new agreement reflects the strong current and anticipated performance of the complex under Brookfield’s stewardship, aligning stakeholder interests, incentivizing ongoing capital investment and enabling the City and State to benefit from that commercial success, generating an estimated $1.5 billion of current value over the lease term.

As part of the agreement, BPCA has secured additional commitments designed to support the future of Brookfield Place and Battery Park City.

Resiliency & Sustainability

Brookfield will commit to reducing emissions and waste with a goal of reaching net zero by 2050 and enhance its reporting on energy and waste usage.

Capital Investments

Brookfield has invested approximately $900 million in Brookfield Place and anticipates investing more than $100 million over the next several years in capital improvements to help attract and retain top-tier tenants and ensure it remains a Class A asset.

Community Benefits & Diversity Contracting

Brookfield will contribute up to $2.5 million for public realm improvements to West Street, set aside up to 10,000 square feet of office space for nonprofits and community organizations, and meet New York State’s Minority and Women Owned Business Enterprises (MWBE) and Service-Disabled Veteran-Owned Businesses (SDVOBs) goals on capital contracts.

Located in Battery Park City, the four original towers of Brookfield Place were developed by Olympia & York as the World Financial Center between 1983-1988. Subsequent to Olympia & York’s bankruptcy in 1992, Brookfield Properties acquired the majority interest in the four original towers of Brookfield Place. In 2013, Brookfield acquired 300 Vesey Street. Over the last decade, Brookfield has invested $900 million to modernize Brookfield Place, including a renovation of the Winter Garden, constructing the east-west passageway linking Brookfield Place with the World Trade Center, and repositioning of the retail at Brookfield Place introducing dynamic new retail and dining offerings. In addition, Brookfield has invested $220 million to modernize and enhance the legacy of World Financial Center office lobbies, mechanical systems and elevators and spent $40 million to modernize and enhance Brookfield Place’s sustainability features. Today, Brookfield Place is one of New York City’s premier mixed-use office and retail complexes and includes five office buildings with heavily touristed retail and dining offerings and tenants such as Royal Bank of Canada, Jones Day, Cadwalader, Invesco, People Inc, and Jane Street Brookfield Place receives million of visitors annually.

BPCA owns the 92 acres that comprise Battery Park City, with all third-party owned buildings within the neighborhood on ground sub-leases to the Authority. The BPCA financing structure supports both the Battery Park City neighborhood — funding maintenance of open spaces, neighborhood beautification and programming, and supporting debt service used to fund portions of BPCA’s capital projects — and the City of New York — contributing to both its General Fund and affordable housing initiatives citywide.

BPCA collects revenue from these ground sub-leases in the form of ground rent, Payments in Lieu of Taxes (PILOT), and other fees. These revenues first fund BPCA’s operating expenses and debt service, with the majority of remaining funds, known as “excess revenues,” annually distributed to the City. The share associated with PILOT (approximately 80 percent of BPCA’s excess revenues) flows to the New York City General Fund and the share associated with ground rent is allocated to a Joint Purpose Fund, the use of which is decided unanimously by the Mayor, New York City Comptroller, and BPCA. In 2024, Governor Kathy Hochul joined Mayor Adams, New York City Comptroller Lander in announcing that BPCA will disburse $500 million in excess operating revenues to New York City’s Affordable Housing Accelerator Fund for the purpose of building affordable housing across the five boroughs. Since 2010, BPCA’s excess operating revenues have contributed more than $460 million in dedicated funding for affordable housing across the five boroughs and helped build or preserve over 10,000 units of affordable housing.

This agreement is the latest action by BPCA to secure long-term stability in the neighborhood. In June 2025, BPCA executed an agreement to preserve and triple the number of affordable apartments at Tribeca Bridge Tower, a 152-unit rental building in Battery Park City. In 2022, BPCA announced an agreement with Rockrose to preserve 70 affordable rental homes in Tribeca Pointe, a Battery Park City apartment building, for nearly 50 years. In 2020, BPCA announced an agreement with Marina Towers Associates to extend a rent protection agreement at Gateway Plaza, Battery Park City’s oldest and largest residential complex, for approximately 600 long-time residents through July 2030.

About BPCA

Established in 1968, The Hugh L. Carey Battery Park City Authority is a New York State Public Benefit Corporation charged with developing and maintaining a well-balanced, 92-acre community of commercial, residential, retail and open space, including 36 acres of public parks, on Manhattan’s Lower West Side. Through execution of its first-ever strategic plan, BPCA works daily toward being an inclusive community, a safe and climate resilient place, a vibrant public space, and demonstrating leadership for the future with a team dedicated to improving service and project delivery. For more info visit: bpca.ny.gov.

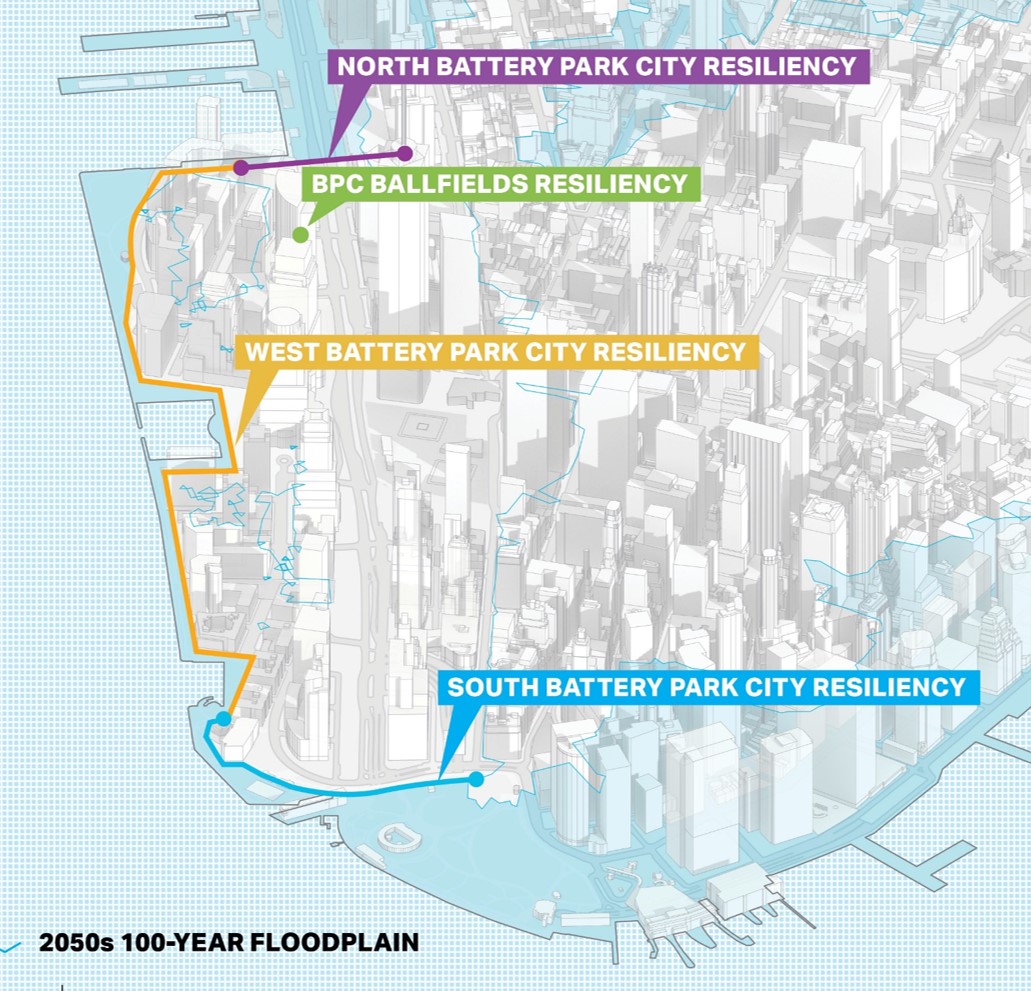

The Battery Park City Authority (BPCA) today releasedThe Case for Resiliency: A Benefit-Cost Analysis for Battery Park City Resiliency Projects for its coastal resiliency work, showing that the benefits of the Battery Park City resiliency projects far outweigh the costs. When considering the total avoided impact on human health and well-being, economic productivity, parks, traffic, building and infrastructural damage, property value losses, and debris removal, the benefit-cost analysis (BCA) demonstrates that for each dollar invested, these projects generate more than $2 in project benefit.

The findings show that for a net present value of $1.6 billion[1] in project costs – across the North/West Battery Park City Resiliency Project (NWBPCR), South Battery Park City Resiliency Project (SBPCR), and the BPC Ball Fields & Community Center Project – there will be $3.5 billion generated in economic and fiscal benefit, or a 2.16 benefit-cost ratio. Following the loss of life and millions of dollars in flood-related damages from Superstorm Sandy across downtown alone, and the outsized impact Lower Manhattan has on the city’s economy, the BCA demonstrates the clear value of undertaking this resiliency work despite construction disruption and related inconveniences.

“More severe and more frequent storms are an unfortunate reality, and we must act with increased urgency in the face of our changing climate,” said BPCA President & CEO Raju Mann. “The Case for Resiliency provides the clearest evidence yet that all of what we’re protecting with our coastal resiliency projects – residents’ health and well-being, jobs, parks, infrastructure, property value, and more – is well worth the years of planning, design, and construction impacts required for implementation. Simply put: Resiliency is a smart, and urgently necessary, investment in New York City’s future.”

Battery Park City and the inland area of Lower Manhattan protected by NWBPCR and SBPCR (together, Battery Park City Resiliency, or BPCR) contain approximately 25,000 residents, approximately 61,000 jobs, and $16 billion in property value. When complete, BPCR will feature a contiguous flood barrier system over 7,900 feet in length, stretching from the Battery, north along the Esplanade of Battery Park City, and terminating at a high point at Greenwich Street in Tribeca.

In addition to providing risk reduction from coastal flooding, stormwater runoff, and heavy rains, BPCR will also bring the following benefits:

– Protection from 2.5 feet of projected sea level rise, help cool neighborhood during heat events, and prevent ponding of more than 1’ depth during rain events;

– Avoided or minimized disruption to existing below and above-ground infrastructure (i.e., water and sewer infrastructure, subways, tunnels, utilities, etc.) from flood events;

– Reduced Homeownership Costs – FEMA’s removal of Battery Park City from the current flood zone will eliminate homeowners’ need to purchase flood insurance for federally-backed mortgagees. Private property owners within the study area should collectively expect to save $1.2 million annually in premiums associated with FEMA’s National Flood Insurance Program;

– Enhanced Public Space – with universal accessibility, remediated circulation pinch points, and increased and improved seating;

– Improved In-Water Habitats – approximately 1,200 linear feet of reconstructed bulkhead designed to provide environments that support marine life.

As illustrated in the following charts, the report quantifies BPCR’s benefits by considering avoided expenditures as a result of the resiliency work. The full report is available here.

“Here is the evidence that while these projects can cause initial sticker-shock, they are smart investments that double in pay-back in broader economic benefits, including saving critical housing, jobs, and keeping our communities safe for the next generation,” said Mayor’s Office of Climate & Environmental Justice Executive Director Elijah Hutchinson. “State and federal support for advancing projects like these are critical for the entire New York harbor and regional economy.”

“The Battery Park City Authority’s ongoing and tireless work to protect our Lower Manhattan communities from severe flooding is once again delivering extensive benefits to the area,” said Congressman Dan Goldman. “In addition to the protection and risk reduction these projects provide New Yorkers, they are projected to yield exceptional financial returns for our city and its residents. The coastal resiliency work being executed by BPCA, under the leadership of CEO Raju Mann, is the gold standard for any climate and resiliency project, and I look forward to continuing to work alongside them in order to protect our city from flooding hazards.”

“Superstorm Sandy showed us firsthand the devastating impact of climate change on our communities, and the path forward is clear: we must act now to protect what matters most,” said Assemblyman Charles Fall. “The findings of this report reaffirm that investing in resiliency is not just necessary but deeply worthwhile – preserving lives, homes, and vital infrastructure for generations to come. This work is about ensuring a safer, stronger, and more sustainable future for every New Yorker.”

“Lower Manhattan has faced the devastating impacts of climate change firsthand, and this analysis makes it clear: investing in resiliency is not just about protecting our neighborhoods today, but securing a sustainable and thriving future for generations to come,” said Council Member Christopher Marte. “These projects are a testament to the power of smart planning and a commitment to safeguarding our city’s residents, economy, and environment.”

“This analysis reinforces what we’ve long known: investing in Lower Manhattan’s coastal resiliency is both cost-beneficial and an urgent regional priority,” said Josh DeFlorio, Chief of Resilience & Sustainability at the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. “In addition to safeguarding the homes, businesses, and parks that make Battery Park City so vibrant, this project will serve as a welcomed supplement to the Port Authority’s own robust resiliency investments at the World Trade Center campus and PATH, providing even more peace of mind to users of our iconic facilities. The Port Authority is proud to support this important initiative and looks forward to continuing our collaboration with the BPCA to secure a resilient, revitalized Lower Manhattan for generations to come.”

“The Downtown Alliance supports Battery Park City Authority’s leadership in climate resiliency and the crucial role it will play in the future of Lower Manhattan as we face the uncertainties of a warming planet,” said Jessica Lappin, President of the Downtown Alliance. “The Case for Resiliency shows the many long term benefits of this project for our neighborhood.”

“The results are clear: Battery Park City’s Coastal Resiliency project pay huge dividends. It is outstanding to see such a rigorous analysis give even more proof that investing in climate resilience pays off,” said Cortney Koenig Worrall, President and CEO of the Waterfront Alliance. “A WEDG® (Waterfront Edge Design Guidelines) verified project, the Waterfront Alliance is thrilled and we call for similar analyses to be conducted by public and private entities for current and future investments. We must make the case for resilience and this is a huge step in that direction.”

“The vitality of Stuyvesant High School is deeply connected with the health and sustainability of the neighborhood surrounding its campus,” said Dr. Seung Yu, Principal, Stuyvesant High School. “The Battery Park City resiliency projects will help ensure that Stuyvesant High School remains a prominent and permanent center for excellence in lower Manhattan. BPCA’s commitment to preserving and enhancing the local environment enables the school to focus on its mission of providing an exemplary education for young people across New York City.”

“In addition to saving taxpayers substantial sums, the South Battery Park City Resiliency Project will provide outstanding opportunities for cultural programming on climate change to spark civic awareness and engagement,” said Miranda Massie, Founder and Director of The Climate Museum. “We are delighted by the release of this benefit-cost analysis and look forward to collaborating with the Battery Park City Authority to create rich shared experiences for the Battery Park and broader New York City communities.”

“The Benefit Cost Analysis of the Battery Park City Resiliency projects spotlights the indisputable benefits for communities that undertake climate adaptation work, setting an economic benchmark and precedent that is likely to have an impact across the tri-state area and beyond,” said David Erdman, Founding Director, Center for Climate Adaptation. “By coupling the urban vitality, health and wellness of its residents (human and non-human) for dense, vibrant, coastal living within a sound financial framework, the BPCA has demonstrated the social, economic and ecological wisdom of their resilience projects.”

“Congratulations to the BPCA on the delivery of the 2025 Benefit-Cost Analysis for its resiliency project work,” said Lance Jay Brown, FAIA, DPACSA, Co-Founder and Past President, Consortium for Sustainable Urbanization. “In pre-Sandy 2011, when we founded the AIA New York Chapter’ Design for Risk and Reconstruction Committee, our first speaker was the highly respected geophysicist, Klaus Jacob. He was chosen for his early work on SLR sea level rise and when he finished his presentation, he estimated that funds spent on disaster preparedness would have up to a 6:1 ratio of return against future damage. Since then, estimates have ranged from between 2:1 and 7:1 based on circumstances. It is totally gratifying to read the BPCA BCA report and the careful and what may well be conservative conclusion presented. This well-designed project and precedent analysis, so professional and detailed, should serve to encourage others contemplating similar investments to proceed with their projects both expeditiously and with confidence.”

“As the Museum of Jewish Heritage continues our mission to preserve memory and inspire action, we are proud to partner in the efforts to safeguard our community and cultural spaces from the increasing threats of climate change,” said Jack Kliger, President and CEO of the Museum of Jewish Heritage. “The findings of this benefit-cost analysis underscore the critical value of Battery Park City’s resiliency projects – not only for their economic and environmental benefits but for their role in protecting the well-being of future generations. Together, we are building a more resilient Lower Manhattan that honors the past while safeguarding the future.”

“As a longtime member of the Battery Park City community, Asphalt Green remembers well the devastating effects Hurricane Sandy had on our facilities and our neighbors,” said Jordan Brackett, CEO of Asphalt Green. “We are grateful for the BPCA’s dedication to safeguarding the long-term sustainability of our vibrant downtown community.”

“BPCA’s efforts to quantify the costs and benefits of these coastal resilience projects can inspire proactive investment into the future,” said Anne Baker, Chief Program Officer at the American Flood Coalition, a nonpartisan organization with over 450 coalition members across the country advancing solutions to the country’s toughest flood adaptation challenges. “As communities across the country – from big cities to small towns – seek to make smart investments in flood solutions, every local example of measurable costs and benefits can help inform those important decisions.”

METHODOLOGY

Since the project costs and benefits do not occur simultaneously, the report adjusts both to a common point in time to determine the BCA, a combined economic and fiscal benefit-to-cost ratio. The $1.6 billion in costs includes initial construction costs, ongoing maintenance and operations and long-term rehabilitation and replacement costs. The $3.5 billion in benefits includes $2.8 billion in economic benefits and $724 million in fiscal benefits. This nets to a combined economic and fiscal benefit-to-cost ratio of 2.16; or, for each $1 invested, the BPCR generates more than $2 in benefit.

ABOUT BATTERY PARK CITY’S RESILIENCY PROJECTS

South Battery Park City Resiliency – Currently under construction at a cost of $296 million, the

South Battery Park City Resiliency Project (SBPCR) will create an integrated coastal flood risk management system extending along the northern border of Battery Park, across Pier A Plaza, through a rebuilt Wagner Park, and to the Museum of Jewish Heritage. The centerpiece of SBPCR is an elevated, resilient, and universally accessible Wagner Park, scheduled to re-open to the public in summer 2025. In 2024, SBPCR earned prestigious Waterfront Edge Design Guidelines (WEDG) Verification from the Waterfront Alliance. The gold standard for waterfront design, WEDG is an award-winning national rating system and set of guidelines for resilient, ecological, and accessible waterfront design.

North/West Battery Park City Resiliency – Tying into the northernmost section of SBPCR, behind the Museum of Jewish Heritage, the North/West Battery Park City Resiliency Project (NWBPR), now in design, will provide risk reduction to property, residents, and assets within the vicinity of Battery Park City and western Tribeca. This integrated coastal flood risk management system will run from just above the Museum at First Place, north along the Battery Park City Esplanade, across to the east side of West Street/Route 9A, and terminate above Chambers Street at a high point on Greenwich Street. In addition to providing risk reduction from coastal flooding, stormwater runoff, and heavy rains, NWBPCR will also bring with it more landscape – over 30% increase in total planting coverage within the project area; and an 85% increase in native plantings – better supporting birds and pollinators with new planted areas that shorten existing gaps in habitat corridors. Construction is scheduled to begin in late 2025 take approximately five years to complete.

The Battery Park City Ball Fields sustained significant damage as a result of during Hurricane Sandy. The now complete BPC Ball Fields & Community Center Resiliency Project consists of an 800-linear foot barrier system to protect the 80,000-square-foot playing surface – used by some 50,000 local youth annually – as well as the adjacent community center from the risks associated with storm surge and sea level rise. The BPC Ball Fields and Community Center Resiliency Project is the 2023 recipient of the American Society of Civil Engineers Metropolitan Section’s Sustainability Project of the Year award. This award is presented in recognition of a project which exhibits innovative environmentally sustainable aspects that benefit its users and the public.

Governor Kathy Hochul, Mayor Eric Adams and New York City Comptroller Brad Lander today announced a $500 million dollar investment from the Battery Park City Authority’s Joint Purpose Fund to build and maintain affordable housing across New York City. Through an agreement between the BPCA, the Mayor, and the Comptroller, the BPCA will disburse $500 million in excess operating funds to New York City’s Affordable Housing Accelerator Fund for the purpose of building affordable housing.

The agreement builds on commitments by Governor Hochul, Mayor Adams and Comptroller Lander to address the housing crisis, build safer, more stable and more affordable homes, and reduce housing costs for New Yorkers.

“When it comes to building the affordable homes that New Yorkers deserve, my administration is leaving no stone unturned,” Governor Hochul said. “This agreement will turn excess funds from the Battery Park City Authority into a massive $500 million investment to help New York City realize its housing potential. From our landmark budget agreement to tackle the housing crisis to transformative investments that get housing built, I am continuing to work with partners like the BPCA, Mayor Adams and Comptroller Lander and fighting for a more affordable and more livable New York.”

The BPCA is a New York State public benefit corporation charged with operating, maintaining, and improving Battery Park City, a 92-acre community of residential, commercial, retail, and open space in lower Manhattan. As Battery Park City was being developed, the BPCA entered into long term ground leases with developers, generating lease revenue from commercial and residential buildings that serves as the primary source of funding for this affordable housing commitment.

Today’s Joint Purpose Fund agreement succeeds the previous agreement for the disbursement of BPCA’s excess operating revenues, which since 2010 has contributed $461 million in dedicated funding for affordable housing across the five boroughs and helped build or preserve over 10,000 units of affordable housing.

New York City Mayor Eric Adams said, “To solve a generational housing and affordability crisis, every sector has a role in providing relief to working-class New Yorkers. Today’s announcement takes us one step closer to delivering that relief. Our administration and our partners are united by a common cause: building more affordable housing. The only way to solve these dual crises is to simply build more, and with this $500 million commitment, we are coming together to use our dollars to make a difference and better support working-class New Yorkers.”

New York City Comptroller Brad Lander said, “Financing the production of affordable housing remains the City’s most powerful tool in combating the city’s housing affordability crisis. This landmark $500 million investment will help ensure that New York City and State have the resources we need to effectively deliver safe and affordable housing to New Yorkers.”

BPCA Board Chair Don Capoccia said, “I’m proud that as a result of the strong financial stewardship of Battery Park City we’re in a position to recommit to address New York’s affordable housing challenges. I want to thank the Governor, Mayor, and Comptroller for their partnership in this effort and for ensuring this money will all go to building and preserving affordable housing.”

BPCA President and CEO Raju Mann said, “Battery Park City Authority has a legacy of funding affordable housing across New York, and we’re thrilled to build on that legacy today. We’re facing a housing crisis and this $500 million will help create stable affordable housing for thousands of New Yorkers.”

BPCA owns the 92 acres that comprise the neighborhood, with all third-party owned buildings within Battery Park City on ground sub-leases to the Authority. The BPCA financing structure has, since its inception, supported both the Battery Park City neighborhood – funding maintenance of open spaces, neighborhood beautification and programming, and supporting debt service used to fund portions of BPCA’s capital projects – and the City of New York – contributing to both its General Fund and affordable housing initiatives citywide.

BPCA collects revenue from these ground sub-leases in the form of ground rent, Payments in lieu of Taxes (PILOT), and other fees. These revenues first fund BPCA’s operating expenses and debt service, with the majority of remaining funds, known as “excess revenues,” annually distributed to the City. The share associated with PILOT (approximately 80 percent of BPCA’s excess revenues) flows to the New York City General Fund and the share associated with ground rent is allocated to a Joint Purpose Fund, the use of which is decided unanimously by the Mayor, New York City Comptroller, and BPCA. In this way, BPCA has played a direct role in promoting the construction of affordable housing in Battery Park City, as well as contributed money to New York’s City’s affordable housing programs, for decades.

New York State Homes and Community Renewal Commissioner RuthAnne Visnauskas said, “This $500 million investment in affordable housing is a true testament to cooperation between our government partners. Investments like this complement Governor Hochul’s housing plan that prioritizes increasing our housing supply and making New York a more affordable place to live. We look forward to continuing our work with Mayor Adams, Comptroller Lander, and the BPCA as we tackle the housing crisis.”

New York City Deputy Mayor for Housing, Economic Development, and Workforce Maria Torres-Springer said, “Our administration is dedicated to solving our housing crisis by building together with partners across government. This historic investment with our administration, Governor Hochul, Comptroller Lander, and the Battery Park City Authority meets the moment, provides affordable housing for New Yorkers, and advances our moonshot goal of 500,000 new homes for New Yorkers by 2032.”

New York City Housing Development Corporation President Eric Enderlin said, “As New York City’s housing crisis deepens and the cost to build new affordable housing continues to rise, we appreciate the efforts of our city and state leaders in securing new and innovative financing sources essential to increasing our housing supply. We look forward to collaborating with our partners to leverage this vital funding and provide more housing for New Yorkers.”

New York City Department for Housing Preservation and Development Commissioner Adolfo Carrión Jr. said, "This multi-year $500 million investment in affordable housing is an agreement that will do more than build more brick-and-mortar buildings, it will transform lives and create new futures for individuals and families waiting for secure, affordable housing. Today, in collaboration with city and state leaders, we recommit and extend this partnership to collectively do all we can to tackle the housing crisis. When considered alongside recently secured state legislative tools, a significant city investment in housing funding from the adopted budget, and the possibility of once-in-a-generation zoning changes to accelerate construction and supply, we have a roadmap that puts us in the direction we need to create the housing access we deserve.”

New York City Executive Director for Housing Leila Bozorg said, “Building and preserving more affordable homes is an absolute priority in the face of our ongoing housing crisis. I extend my sincere appreciation to Mayor Adams for his clear-eyed leadership on investing in housing, and to Governor Hochul, Comptroller Lander, and the Battery Park City Authority for this meaningful partnership that aims to make affordable housing options in our city more abundant.”

State Senate Majority Leader Andrea Stewart-Cousins said, “Housing was unequivocally at the forefront of this legislative session, and we’ve worked tirelessly to ensure that every New Yorker has access to safe, affordable housing. The years of stagnation in the building of new affordable housing in New York State has come to an end. This $500 million investment will continue our ongoing commitment to boost our housing supply and revitalize our existing affordable housing stock. As Majority Leader, I am proud to support initiatives that prioritize affordable housing, ensuring all New Yorkers have a place to call home. I would like to thank Governor Hochul, Mayor Adams, and NYC Comptroller Lander for their partnership and work to secure this important investment.”

State Senator Brian Kavanagh said, “This allocation of $500 million continues an important long-term commitment by the State, the City, and the Battery Park City Authority to support our efforts to ensure that all New Yorkers have access to safe, affordable, and sustainable housing. I thank Governor Hochul, Mayor Adams, Comptroller Lander, and BPCA Director Raju Mann for their leadership and dedication to addressing the housing crisis. I look forward to continuing to work with them, with our colleagues at all levels of government, and our communities to help ensure that this funding has the greatest possible impact, and particularly to identify opportunities to increase affordability in Lower Manhattan.”

Assemblymember Charles D. Fall said, “I am extremely pleased to see the significant $500 million investment in affordable housing announced by Governor Hochul, Mayor Adams, and Comptroller Lander. This is a vital step in tackling the housing crisis and ensuring that New Yorkers can access stable, affordable homes. The decision to allocate funds from the Battery Park City Authority’s Joint Purpose Fund highlights a strong commitment to leveraging available resources for the public benefit. We know that affordable housing is a pressing concern in our city, and this investment will greatly ease the burden on many families facing financial struggles. I am particularly glad that this initiative will support 5 World Trade Center and the surrounding district, areas that have long needed affordable housing solutions. I look forward to seeing the positive impact this funding will have on our communities and residents.”

Assemblymember Linda B. Rosenthal said, “When a pot of $500 million is released to go toward the construction and preservation of affordable housing in New York City it is an auspicious moment and a time to applaud and start planning. When the funding is allocated in the midst of an affordable housing crisis, it is a time to cheer and become more hopeful about catching up to the desperate need for affordable housing., said Assemblymember Linda Rosenthal, Chair of the Assembly Housing Committee. I am thankful that Governor Hochul, the Mayor and Comptroller have designated the funding in the Battery Park City Authority Joint Purpose Fund for such a useful purpose, and look forward to seeing new safe, secure and affordable units spring up in all parts of the City.”

Manhattan Borough President Mark Levine said, “Every dollar that we can put toward affordable housing will make for a more livable New York. Today’s announcement marks a transformative investment in New York’s housing stock. Tackling the city’s affordable housing crisis takes creative solutions, and I’m grateful to the BPCA, Governor Hochul, Mayor Adams, and Comptroller Lander for their leadership on this.”

New York City Council Member Christopher Marte said, “We are thrilled by the leadership of Governor Hochul and Comptroller Lander in enacting this policy that the community has long been asking for. Battery Park City Authority generates a lot of revenue, mostly from its residents, who have been asking that their contributions go towards a meaningful source – not just the general fund of the city. NYC is facing an affordability crisis, and this excess funding and massive investment can go a long way to meeting the urgent need of New Yorkers who are facing ever-rising rent. We are hopeful that some of this affordable housing can be built in Battery Park City itself, as this neighborhood continues to grow and thrive.”

Chair of Manhattan Community Board 1 Tammy Meltzer said, “Building socio-economic diverse housing in every neighborhood is an essential component for ensuring the resilience of New York City and all its communities. We are thrilled that all disbursements of BPCA’s excess operating revenues will be dedicated to funding affordable housing. CB1 looks forward to collaborating with our Elected Leadership to identify ways to restore affordability in areas that have lost thousands of affordable housing units, like Lower Manhattan and hope the funds facilitate housing stability for New Yorkers who want to work and live here.”

Governor Hochul’s Housing Agenda

Governor Hochul remains committed to increasing the supply of safe, stable, and affordable housing across New York and reducing housing costs for all New Yorkers. As part of the FY25 Enacted Budget, Governor Hochul fought to secure a landmark housing agreement to increase New York’s housing supply by incentivizing new housing construction, including affordable rental housing and homeownership opportunities, in New York City; extending the construction deadline for projects in the now-expired 421-a incentive program; encouraging affordability in commercial to residential conversions in New York City; authorizing New York City to lift outdated restrictions on residential density in New York City; and creating a pathway to legalize existing basement and cellar apartments in certain areas of New York City.

In addition, as part of the FY23 Enacted Budget, the Governor announced a five-year, $25 billion Housing Plan, to create and preserve 100,000 affordable homes statewide. More than 40,000 homes have been created or preserved to date.

Capital Projects

Executive Team

Pamela M. Frederick

Goldie Weixel

Heather Fuhrman

Executive Board

Resiliency & Sustainability

Talk to us

Have questions? Reach out to us directly.

Donald Capoccia is the managing principal and founder of BFC Partners, a real estate development company that has been involved in the planning, development and construction of some 12,500 units of housing in New York City with a combined value of $4.5B. His projects also include approximately 2,000,000SF of neighborhood retail and community facility uses. Mr. Capoccia began his development and construction activities in New York City in 1982, just prior to the completion of a Masters Degree Program in Urban Planning at Hunter College, and after completing a BA in Urban Studies from the University of Buffalo in 1979. Mr. Capoccia and BFC have focused predominately on the production of affordable housing, investing in a concentrated geographic strategy that has helped spur the resurgence of key New York City neighborhoods; the East Village, East Harlem, Williamsburg and Downtown Brooklyn. Mr. Capoccia has pioneered the production, and promoted the importance of affordable home ownership opportunities to these neighborhoods.

Donald Capoccia is the managing principal and founder of BFC Partners, a real estate development company that has been involved in the planning, development and construction of some 12,500 units of housing in New York City with a combined value of $4.5B. His projects also include approximately 2,000,000SF of neighborhood retail and community facility uses. Mr. Capoccia began his development and construction activities in New York City in 1982, just prior to the completion of a Masters Degree Program in Urban Planning at Hunter College, and after completing a BA in Urban Studies from the University of Buffalo in 1979. Mr. Capoccia and BFC have focused predominately on the production of affordable housing, investing in a concentrated geographic strategy that has helped spur the resurgence of key New York City neighborhoods; the East Village, East Harlem, Williamsburg and Downtown Brooklyn. Mr. Capoccia has pioneered the production, and promoted the importance of affordable home ownership opportunities to these neighborhoods.